Open data as a concept is relatively straightforward. In this digital era every library I know has a website, usually paired with an online catalogue allowing users to search the library's collection, and increasingly there are more libraries engaging users via the many social media channels available. I'm sure almost everyone has heard the phrase 'content is king!' It's clear we understand that it is necessary to present our libraries online.

Open data takes the idea of publishing content online one step further. Instead of simply publishing content online, champions of open data are encouraging the publication of data - structured, machine-readable information.

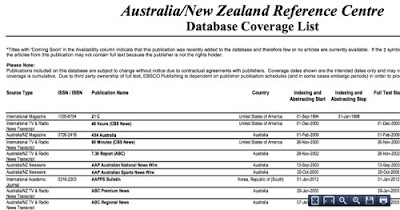

So what's the difference? Let me give you an example. Say you want to find out whether a particular journal is available in full text in any of your library's databases. Sure you can visit Ebsco's website and download the title lists for each of their products in a number of formats (a grab from the PDF for ANZRC is shown below) but which database is it in? The title you are looking for may be in any of their products and you need to download them all one at a time and read through each one to find out. This is what I call content.

Open data is simply content that is published as machine readable data, in such a way that other people can use it to make new things. Taking our example above, open data about which journal titles are indexed in which databases would be far more useful to anyone trying to answer our question. A simple title or ISBN search could provide the answer we're looking for.

David Eaves' Three Laws of Open Government Data is one of the most widely quoted articles on what makes data open and it is worth repeating those laws here.

The Three Laws of Open Government Data:

- If it can’t be spidered or indexed, it doesn’t exist

- If it isn’t available in open and machine readable format, it can’t engage

- If a legal framework doesn’t allow it to be repurposed, it doesn’t empower

Of course, when looked at in this way, the information about materials in library collections has been stored as data ever since we've had automated library systems. Indeed, users can visit our catalogues and query our collection data. The information about our collection is stored in a machine readable format - the MARC record.

MARC records, hmmm...

Sure MARC is a machine readable format, it says so in the name (machine readable catalogue) but it's a bit of an antiquated format that no other industry uses. It is a structured format designed to describe books. In my opinion though, it is outdated and of little relevance to the current trend of sharing on the web. MARC is extremely granular in the structure it provides for describing books with its leaders, fields and subfields for things like the number of pages of plates or whether the book has an index. But it is woeful at describing the other types of materials that are now part of library collections, particularly the digital materials that are increasingly prevalent. In fact some of the more desirable information attached to your catalogue records, such as summaries, excepts, tables of content, reviews, permalinks, etc., is consigned to notes fields and the like as MARC is so old this information was not even a consideration in its design.

To web developers that are used to working with APIs providing data in web ready formats like XML and JSON, MARC records may as well be a PDF. This is so evident, and the need for a better format is so clear, that many library system vendors are now baking in RSS (a widely used xml format) as an output format for searches performed against the data in their system.

The difference between searching an online library catalogue and viewing the results on a web page versus receiving those same results as an RSS feed is the difference between content and data. Don't get me wrong, content is still important and most library users will interact with our collections through the content that is accessed via the online catalogue but data can have a life of its own.

Although the term may be new to some librarians, the concepts shouldn't be much of a stretch to accommodate. But why should libraries make the effort to provide open data? In my opinion, there is a simple answer.

You just can not imagine the cool things other people can and will do with your data.

There are parts of our collection that are under-used because they are inaccessible or poorly described, and thus difficult to discover. There are hyper-local things that public libraries in particular collect that just aren't available anywhere else. This material when provided as open data can be made far more interesting and useful by people that are cleverer that you or me.

There are web developers out there who can take your data out of the bubble of your library and give it new life; put it to use in exciting new contexts and create entirely new ways to discover and experience your collection.

There is a worldwide push for governments to open up their data. We are seeing data catalogues appearing in several countries including Australia. And we are seeing a new type of event spring up around all this newly available data - the Hack Day.

Libraries are getting into the act as well. The first Library Hack event was held in 2011 and the winner produced a series of talking maps that combined photographs, audio recordings and other data and superimposed them onto a map to create a story.

We are seeing some libraries experiment with new ways to present their collections online. The New York Public Library's Map Warper project takes digitised historical maps from their collection and overlays those maps on Google Maps to give a then / now type experience. And our own National Library of Australia's efforts to combine different data sets into the mother of all cultural discovery tools, Trove, is making headlines around the world.

There are many more examples of interesting things happening online with open data. My biggest problem is that I'm not a developer and I'm extremely frustrated that I don't have the skills to build some of these interesting projects myself. What librarians are good at however is classifying objects.

What I can do is create data models and classify objects. And you can help. Together we can create the data sets that people who can do the programming can then turn into unique applications and experiences.

I've started a tumblr to collect our ideas and have conversation about how we can define and create some data sets. I've started it off with an idea of my own but I'm sure you've got plenty more. You can add your own posts and everyone can discuss the ideas right there. Hopefully, we can come up with some projects that will result in something tangible. Maybe someone out there will be able to make something amazing with out data.

So head over to openlibrarydata.tumblr.com and share your ideas, join the conversation and help open our data to the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment